It has been a little over a year since I announced the news that my marketing software startup closed it’s Series B round of funding. The article, “Insanity? Why A Bootstrap Entrepreneur Raised $17 Million in Venture Funding”, was a candid glimpse into the rationale for raising what seemed like a huge amount of money to me at the time (it seemed huge, because it was — at least to me).

Today, we’ve released news that HubSpot has just closed on another $16 million funding round (our Series C) bringing our total capital raised to a whopping $33 million.

As I write this, I’m a bit worried that this article is going to come off as arrogant and/or self-indulgent. I promise that’s not my intent. I’m just going to let you “inside my brain” in the hopes that some of you will find the excursion interesting, amusing or useful. Although not all of you are out raising money (thank goodness!), I thought you might want an insider’s view on why an otherwise rational and pragmatic entrepreneur would make this kind of leap. I promise, the decision to raise this kind of money wasn’t as crazy as you might think.

The Story Of How I Ended Up Raising $33 Million In Funding

1. Did we need the cash? No, we didn’t need the cash. We had over $6 million in the bank. But, if I’ve learned one thing about VC fund-raising it’s that not needing to raise money helps a lot.

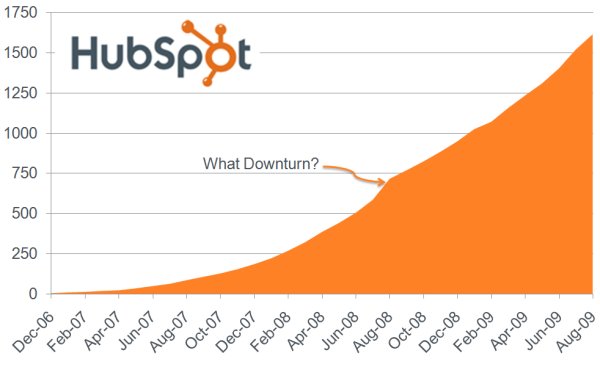

2. Why raise money at all? As the company has evolved, we’ve learned a lot about the mechanics of our business. We have gotten pretty good not just at predicting our growth path — but actually solving for it. There’s no better way to illustrate this than with the graph below:

This graph shows the number of customers (people that pay us money) over time. Note that our revenue curve is even better than this (because the average revenue per customer has steadily gone up over the same period). In short, things have been going pretty well. As we’ve gotten more visibility into the business, we’ve gotten good metrics around the drivers in the business. The two most important are: COCA (cost of customer acquisition) and LTV (lifetime value). We’ve worked hard to ensure that COCA < LTV. And, this margin is getting better over time. Given that we’ve got a decent handle on things, it made sense to further invest in the business so that we can continue to scale it. Once we found a model that works, we figured it would be a good idea to iterate, execute and scale it. As I’ve noted here in the past, we’re swinging for the fences with HubSpot and have not backed off of that position one iota.

3. Should we raise now or wait? OK, fine that we decided to raise money, but why now? Given the state of the economy over the past year, some thought we were raising too early. The business has been growing exceptionally well. The question was: “Why not wait until the economy improves, the business is even further along, and raise at better terms?” That was a good question. Our primary argument was that we didn’t want to wait too long, because the longer we waited, the less leverage we would have (see #1 above). It was not a particularly easy decision. We’ve been fortunate to have great investors in the company (General Catalyst and Matrix Partners) who have been exceptionally supportive. We were reasonably confident that had we waited until next year, we would likely have had no issue raising funds. But, even during our best times, we’re cautiously optimistic at HubSpot. A few factors we were pondering: 1) Would the economy really improve? If so how, when, how much, and for how long? 2) Even if the economy improved, what would the VC industry look like next year? (We had already witnessed a fair amount of shake-out and expected more). 3) Even if things did get better, how much better would the deal be then vs. now? How much should we discount back for risk? 4) How would a “wait until later” approach impact our decision-making in the business right now? Would we take appropriate levels of risk or as time passed, would we start to act with increasingly more conservatism?

After all was said and done, we decided that there was a price (or more accurately a “set of terms”) at which we’d be willing to do a deal now, instead of waiting until later. We were able to beat that “minimum bar” (by a relatively large margin), so it made sense to do something now. Of course, in these situations, it’s never “knowable” as to whether we made the right decision or not. But, we’re relatively comfortable that we at least made a pretty thoughtful decision.

4. Did you really need to raise that much? Not really. Our model and plan called for significantly less than this. But, the other important thing I’ve learned about venture fund-raising is that you should always raise more than you think you need to get to the next milestone. We had a model and plan in place that would make this the last venture round we’d need. But, given the terms on the table, it made sense to leave ourselves some wiggle room and buffer. This increased the probability that we’d be able to get to where we wanted — even if things didn’t quite go precisely as planned (which they rarely do). And, it’s painful to go through the fund-raising process, so if you can condense things into fewer rounds, it saves a lot of pain and agony. We had the opportunity to raise more than we needed, with pretty “entrepreneur friendly” terms — so we took it.

5. What are you going to do with all that money? Well, we’ve always been pretty capital efficient. One quick calculation I’ve been doing in my head since the early days of starting the company is this: Figure out your run-rate annual recurring revenue. Multiply this by some conservative industry multiple (somewhere around 3X). Then, make sure that the total money you’ve “consumed” is less than this number. When it is, you’re basically operating on an “accretive” basis (i.e. the actual enterprise value built — even if sold to a conservative financial buyer — is greater than the amount of money used to build that value). In our case, we’ve been accretive from the early, early days. And, despite our torrid growth, we’re still accretive now (revenues and associated “enterprise value” is growing faster than our rate of capital consumption). So, back to what we’re planning to do with the money: #1 product. #2 product. #3 customer acquisition. We have a backlog of ideas that’s both uplifting and depressing at the same time. There are so many great ideas for how we can deliver more value to our customers. We plan to pick the best of these and execute on them maniacally.

We are out to build the next-generation marketing platform.

6. So what’s next? We’re also on to what we think is a massive opportunity that helps organizations capitalize on the major tectonic shift in the marketing industry. It’s a really, really big deal. But, with radical change comes the need for radical education. And that kind of education takes committment — and capital. We’ve got a burning passion to help people figure out how to better reach their potential customers by pulling them in. This is what caused me to devote most of the Summer to write Inbound Marketing (a book that captures a lot of what I’ve learned about marketing by helping startups and small companies figure out how to “get found”). But, enough about me. Let’s talk abut you. You’re likely in the startup game because you perceive something fundamentally wrong with the world that you know you can make better. I know how you feel. My advice is to dig in, understand the problem as well as you can — and go fix it.

OK, so reading back through the article, it came off as more self-indulgent than I had planned. But, it’s 2:00 a.m. here in Boston and I’m not sure investing more time is going to make the article much better. Such is life sometimes. I trust you’ll forgive me for this lapse. It’s a big day for me and my team at HubSpot. We’ve now got even higher expectations for ourselves than we had before. Like you, we’ll be working hard to live up to those expectations. I’ll close (once again) with my definition of success:

Success = Making those that believed in you look brilliant.

What do you think? Did I do the right thing in raising all this funding or am I just rationalizing my behavior decision? What would you have done?

Oh, and if you're a blogger/journalist/media type and are curious about details or want to write a story, feel free to email me at dshah {@} onstartups.com. Would be happy to chat.