Today’s big news is that my company HubSpot announced a major new round of venture financing. Details can be found in the non-clever, but descriptively titled “Sequoia, Google Ventures and Salesforce.com Invest $32 Million in HubSpot”. We could not hope for a better set of investors for this round, and we’re thrilled with the further marketing validation that this group of investors brings.

My co-founder, Brian Halligan and I have been thinking about the Software-as-aService (SaaS) industry for many years now. It started when we were classmates in grad school back at MIT. We consider ourselves eager students on the subject. As part of this most recent funding round, we dug into more details and want to share some of our insights, lessons learned and data with you. We’ll also share some of the same arguments we made to our new investors.

Lets start things off with a few fun data points.

* At the end of 2010, the median valuation of publicly traded SaaS companies was approximately 4.2x their revenue. (This median was 3.2x in 2009).

* The highest multiples were awarded to Salesforce.com (9.5x) and SuccessFactors (9.6x).

* Size matters. The market seems to value the larger revenue SaaS players more. The companies with revenue above the median had a 5.2x multiple vs. 3.3x for the companies with revenues below the median.

Lesson #1: Winners win big.

We’re going to argue that in the age of the Internet, winners win big. 10–15 years ago, in most technology categories, oligopolies formed. [To save you the Wikipedia lookup on oligopoly, it’s a market where a small number of sellers dominate an industry.] The #1 player in a category would get a decent chunk of the market-cap of the industry, but #2, #3 would have respectable portions too. Basically, the top 3–4 companies would have most of the market power. That seems to have changed. In modern technology-driven industries, over time, the #1 player ends up capturing a very large portion of the mindshare and marketshare.

To demonstrate this, try this short mental exercise. For the following leading companies, see if you can name the #2 player and #3 in their category. You have 30 seconds, I’ll wait:

- Amazon

- NetFlix

- VMWare

- eBay

Difficult, isn’t it? Chances are you struggled a bit with coming up with the #2 and failed completely to come up with #3. The point here is, as these tech categories evolved, the #1 player became so dominant that we often don’t even know who #2 and #3 are.

This is the main reason that HubSpot has been aggressively investing in growing our marketing platform and growing our marketshare and mindshare. Similar to how Salesforce.com dominates the CRM industry, we think there will be one emergent leader in the marketing software industry. We’re working hard to be that company.

Question: Doesn’t this reek of the late 1990s craziness when startups were spending heavily to acquire “mindshare”?

Yes, back in the dot-com days, many startups raised millions of dollars of capital to try and “get big fast” (and be first-mover). But, there’s a big difference today. In the dot-com bubble, companies were investing heavily to acquire “eyeballs” (or some other proxy for value). In our case (and in the case of many SaaS companies), we’re investing in growing revenue (not a proxy for revenue). Like Salesforce.com did in its early years, we understand the economics of our business. We understand how much it costs to acquire a customer, and the lifetime value of that customer. And, for us, Lifetime Value >> Customer Acquisition Cost. So, we don’t think it’s like the dot-com bubble at all. We’re investing capital into building a real business. At HubSpot, we not only have gross margins (gasp!) but they’re trending upwards month after month.

Question: OK, that’s great. But do you really need $50+ million in capital? It’s a SOFTWARE company!

That’s an excellent point. 3–4 years ago, when I was just starting, I thought it was somewhat crazy to even be raising $5 million for a software company (my prior two software startups were self-funded). I never would have believed we’d end up raising $50 million. But, I’ve since learned that it’s not only not crazy to raise this kind of capital, it’s quite possibly necessary. I’ve written about this (and other fun SaaS topics) before in the super-popular article “SaaS 101: 7 Simple Lessons From Inside HubSpot” (it’s been retweeted over 3,000 times!) But, the point bears repeating: SaaS companies often charge on a subscription basis — so cash comes in over time (often monthly). However, the acquisition cost is paid up front. The result is, even if you’re making margin on each sale, the faster a SaaS company is growing, the more cash it will need to fuel that growth.

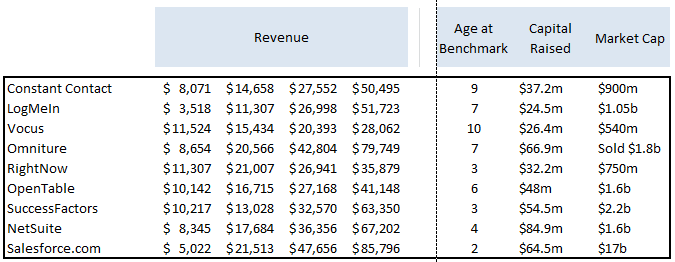

Lets dig into this a bit deeper. Below is a chart that HubSpot created a while ago. It does something interesting — it looks at some prominent, publicly-held SaaS companies and then time-shifts them. The reason we did this analysis was we wanted to understand how our growth, cash burn and fund-raising matched up against other SaaS companies for which there was public data available.

The median (not mean) capital raised prior to the IPO for these companies was $47 million. Of course, going public is not the only measure of success, but it’s interesting that those that did break-out and remained independent consumed significant capital getting there. There are no “bootstrapped all the way through” kind of companies. Don’t get me wrong, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with bootstrapping software companies (I’m at my core a bootstrapping kind of guy) — but I’m going to argue that to create a SaaS market leader in a large segment takes capital. [Side note: Our peers in the industry have also raised tens of millions, presumably for this very reason].

Disclaimer: We’re not investment bankers, and this is not investment advice. This project was done as an interesting side project. Data was taken from available public sources. Don’t rely on our analysis for anything serious.

Question: So, you’re going to spend all the money on sales and marketing?

Actually, no. Last year (before we had even considered raising another venture round), we made a deliberate decision and formed a strategy that we labeled “HubSpot Inc 2.0” (a convenient label for the second-generation of the company — not the product). The primary goal of this new strategy was to shift most of our dollars away from sales and marketing and into product development. The company had been doing exceptionally well acquiring customers, and we felt that the best use of our cash was to make the product even better and produce happier customers. We have a cool measure at HubSpot for customer happiness call the “Customer Happiness Index” (CHI). It’s a regression-analysis based quantitative metric that uses available data about customers and their interactions with the company/product. In any case, when we decided to shift to “HubSpot Inc 2.0” we set very specific goals for ourselves around things like CHI. We’re in the middle of executing on that strategy now (and hiring aggressively in our R&D team).

Big Insight: System dynamics and the sales, marketing, service conundrum.

Here’s a big lesson learned from our HubSpot experience. Think of the four primary areas of a SaaS company as being marketing, sales, product and customer service. (You might call them different things, but that’s roughly right). Now, lets temporarily take product out of the mix and look at just marketing, sales and customer service. Across these three groups, an interesting thing happens. If you try to improve the metrics of one of these groups, one or both of the other groups often suffer. For example, if you’re looking at just decreasing the cost-per-lead (marketing metric), you can easily do that by allowing a higher percentage of leads into your funnel. The result is less “quality” customers — and so the customer service group suffers and your cancellation rates go up. If you try to improve just your retention rate numbers (customer service), you can do that by putting stronger “filters” in your sales group (perhaps reducing commissions on customers that are not ideal”). Of course, that means your sales team is working harder for every deal, and your cost of acquisition/sale goes up. Generally, you can take any of the key metrics for these three groups, and you can improve one metric at the expense of one or more of the others.

The way to break out of that “robbing Peter to pay Paul” conundrum is to invest in the product. If you invest in R&D and make the product better everybody wins. Marketing has an easier job (because you get more referral customeres). Sales has an easier time closing deals, because the product demo sings. Customer service has an easier job because customers are happier with the product (and cancel less). So, economically, investing in the product has the most leverage. That’s why we’re taking so much of our available dollars and pouring them into the product.

Of course, now that we have so much cash we can invest in both. We’ll resume investing in sales and marketing too. The economics of our business makes fundamental sense. No reason not to get even more customers. We have a dominant position in the marketing automation industry today (with 4,000 customers, we have more than all of our competitors combined) and it makes sense to extend our lead. We also have customers in over 30 countries today — and we’d like to deepen that footprint.

One of the core values at HubSpot is transparency (we have others too, but that’s a topic for another article). So, within reason, I’m happy to answer questions and share things we’ve learned. We don’t have alll the answers, but we usually have opinions. What would you like to know about our take on SaaS?

* Some of the data in this article was based on the Software Equity Group annual report, 2010.